#StudentLife

Benefits of Being a Research Participant

Adventures in Research

Social interaction, speech samples, smelling sticks, EEG, electric shock, surveys, fMRI scans, eye-tracking, skin conductance response, receptor blocking – as a frequent research participant, I’ve tried it all, and more. It’s become kind of a hobby of mine.

There are a number of reasons why I do it, from the compensation to loftier ambitions of finding representation in the data, but the biggest incentive for me these days, as a second year master’s student in Multilingualism at the University of Oslo, is that participating in research is an opportunity to learn more about how research – and especially language research – is done.

Compensation

Most experimental (in other words, lab-based) studies compensate participants in some way, usually with a gift card, and there are actual tangible benefits to be gained. Signing up for more intensive research studies back home in the U.S., for example, helped me to fund my move here to Oslo in the first place. I was able to work my full-time job and do part-time gigs while also completing a daily log that tracked select physiological responses. Once a week, while a researcher supervised me over Zoom, I filled a vial with blood and carefully plucked a hair sample. On my Friday lunch break, I’d drop these off at the lab, along with a urine specimen. Over an eight-week period, I made about NOK 8 500 (paid to a Visa gift card) with a not unreasonable amount of effort.

The majority of compensated studies that I have participated in here in Norway involve one of two different payment methods: GoGift and Universal Presentkort. GoGift allows you to select gift cards in different amounts that can be applied towards a variety of vendors. Having been my mother’s caregiver through almost a decade of Stage IV breast cancer, for instance, I spent a few hours answering questions on end-of-life decisions. Not only were the questions thought provoking, allowing me to reflect on issues that don’t typically come up in conversation, but I was able to convert my GoGift voucher into tickets to the Daði Freyr concert at Rockefeller and a donation to my favorite non-profit organization. I also got a chance to pay forward some of the benefits that my mom received from others who contributed their time and bodies to cancer research.

Universal Presentkort also works with a variety of vendors, including book, clothing, hardware, and even some grocery stores and restaurants. A prominent hotel chain was recently added to the mix, so I’m currently trying to save up points for a trip that would enrich my current studies. My ultimate goal, however, is to be able to just have gift cards in my wallet so that I can give them to people in need that I meet on the street. The cards can be used right at the cash register, so don’t need any special sign-ups or digital activation in order to access.

My ultimate goal, however, is to be able to just have gift cards in my wallet so that I can give them to people in need that I meet on the street.

The going hourly rate of compensation for one’s time seems to be about NOK 200, though this varies depending on how intrusive the study is and how difficult it is to recruit participants. Multi-session studies often offer a little bonus amount as an incentive to complete the entire course of participation. The nice thing about being a student is that lab studies tend to be located on-site at the University, so you can schedule around classes and meetings when you’re already there. Only a short distance away is the BI Research Center in Nydalen, where research participants are compensated via Vipps (sign up for the participant pool here).

Not all studies are compensated financially, though, and this is usually true regarding research of a more qualitative nature. These types of studies tend to have a much smaller sample size, with the aim of going deeper into the attitudes, experiences, and perceptions of study participants. People tend to join this kind of research to satisfy their curiosity, contribute to community knowledge, or for other personal reasons.

Personal Meaning

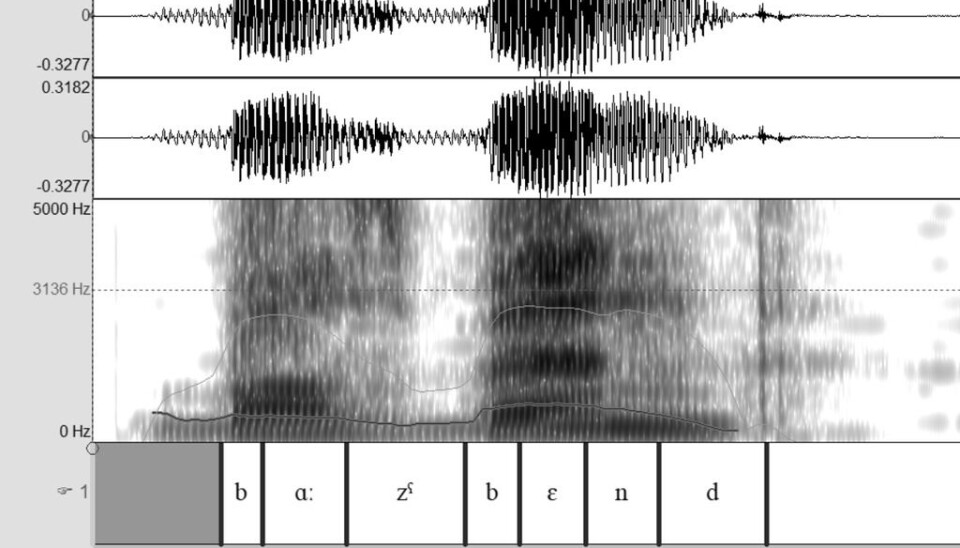

One of the most remarkable experiences I’ve had as a research participant was that of rediscovering myself during a linguistic methods class. As someone who had grown up speaking Norwegian in the United States, I once volunteered to do an hour-long interview with researchers from the University of Oslo who were visiting my town. We sat in a cozy office over coffee and they videoed the conversation while we spoke (in Norwegian) about my general background and how I ended up learning Norwegian in the first place.

I forgot about the experience for almost exactly a decade, only to feel a dawning sense of recognition when the topic in class turned towards speech samples and investigating language change over time and geography. We had some time to explore the database on our own in class. Sure enough, there was me – ten years younger, phonetically transcribed with a waveform spectrogram, and completely oblivious to the fact that I’d one day move across the ocean myself to study issues related to language and migration.

By coincidence, in class that day was someone who remembered this period of data collection. A lot of study participants during this data collection trip were older, I learned. It was an emotional experience for some, because it had been so long since they had spoken Norwegian to another human being. I recognized this – as a little girl, I belonged to several Scandinavian heritage groups in my area. We performed songs and folk dances at nursing homes and older residents were often delighted to learn that, as a young person, I had the language in me, too.

I spent a lot of time with immigrants of my grandmother’s generation when I was a child. From this perspective, I understand the unique sense of isolation that can descend when one’s native language circle begins to dwindle, and the unique burden it places on younger speakers to keep hold and bear witness to a fading past. It matters to me that this is represented in the research, because migration, language change, language shaming, language discrimination, and language loss are not just historical glitches, but very real circumstances with significant impact on quality of life.

“Researchers are shaped by their personal backgrounds and life experiences, which might influence the questions we ask, how we engage with societal concerns, and how we position themselves,” says Pia Lane, a professor at the University of Oslo’s Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan (MultiLing). “I was raised in a multilingual household where Norwegian, Kven, and Sámi were spoken by adults, but they only spoke Norwegian with their children. This led me to study why and how this language shift happened. Later I was involved in developing a written standard for the Kven language, and I looked into how people related to the new standard.”

Seeing transformation happen over time can be powerful. Pia reflects, “When I started my research in my home community, the Kven language was still seen as inferior by many. This is dramatically different now – people sign up for Kven courses and young Kven take an interest in their language and culture. These developments have come about through the actions of the Kven people. I cannot take credit for this change, but I hope that my research and engagement have contributed to this positive change.”

Benefit to Society

In general, participating in studies is an important contribution to knowledge development. The more people we can test, the better our chances to make correct generalizations about language development and processing and the cognitive, social, and environmental factors that play a role.

I reached out to Franziska Köder, a researcher and lab manager of MultiLing's Socio-Cognitive Laboratory at Henrik Wergelands Hus, to learn more about how participation can translate into societal benefits. Franziska tells me that researchers here “investigate how people learn, use, and process one or more languages. The lab offers a wide range of technologies such as eye-tracking, EEG, and audio or video recordings, and many studies combine multiple methods to answer their research questions.”

Franziska says, “In general, participating in studies is an important contribution to knowledge development. The more people we can test, the better our chances to make correct generalizations about language development and processing and the cognitive, social, and environmental factors that play a role. A concrete example of research that benefits society is the research project of PhD student Anne Marte Haug Olstad. She has co-developed a digital language game that helps school-age children who have newly arrived in Norway to practice their Norwegian pronunciation. For many studies with children, we also need adult control groups to get a better idea of the developmental trajectory.”

“A diverse set of participants comes to our lab, from infants to elderly people, neurotypical people and people with disorders such as ADHD or dementia,” she elaborates. “We have, for instance, a study in the lab that looks at differences in reading patterns between young adults with and without ADHD. Another project investigates how bilingual Polish-Norwegian toddlers process words compared to monolingual Polish or Norwegian children.”

Just a little over five minutes away at Helge Engs Hus, Athanasios Protopapas (better known as Thanassi), a professor in the Department of Special Needs Education, is interested in understanding the cognitive mechanisms of reading fluency. “One relatively unexplored topic we are interested in concerns the so-called ‘eye-voice span,’ that is, when reading aloud, the distance between the word you utter and the word currently looking at. Fluent readers have long been known to look ahead, and this is necessary in order to read with good prosody. We know readers regulate this distance tightly, but we do not really know what governs and modulates it. In our current project, we provide a reading fluency intervention to children in 2nd and 5th grade and aim to see – among many other things – whether and how this distance is affected.”

“Everyone agrees that achieving reading fluency is critical not only for academic success in school but also for future development,” says Thanassi. “From the moment one learns to read in the first school grades, one must keep reading to learn things, both in school and later; plus, with the advent of social media, reading has invaded all aspects of social life for the new generations. Thus a lack of reading fluency can be crippling in even more pervasive ways than in the past.”

“Researchers know a lot about how to measure reading fluency, and to some extent what can be done to increase it a bit, but we understand surprisingly little about the cognitive mechanisms underlying it.” Thanassi’s hope “is that shedding light under the hood and achieving a better theoretical understanding of what goes on, and what could go wrong, could lead to more efficient instructional programs and interventions in the future.”

A little further down, at Harald Schjelderups hus, Julien Mayor, a professor in Health, Developmental and Personality Psychology, is “interested in how babies learn their language(s). What, in their learning environment (parental speech, dialectal exposure, activities such as shared book reading, pacifier use, etc.) makes them learn words better, and what does not? In our baby-friendly BabyLing lab, at the Department of Psychology, we conduct research with babies and their caregivers to find out!”

“I also develop new language screening tools that help diagnose potential language delays and impairments among young children,” says Julien. “These types of lab-based empirical studies are instrumental in uncovering the learning mechanisms that young children employ when learning words and perceiving sounds of their language(s) ... such that all young children can benefit from the best learning environment for them – and develop strong communication skills, a central aspect of human life throughout the lifespan.”

Promoting Diversity and Statistical Power

When I think about what research can show us about the human experience, I like to think that my experiences and critical aspects of who I am – gender, age, socioeconomic background, education, etc. – are represented in this body of knowledge. At a minimum, research should reflect the population it serves. I also believe it’s important to help strengthen the impact of a study by contributing to the numbers.

I asked Natalia Kartushina and Peng Li, two of the team members putting together the Birth of an Experiment in Language Science summer school at MulitLing, about the importance of having a good participant pool to draw from. “The aim of a research project is to answer a research question(s) and to reach a conclusion that would apply to many of us,” says Natalia, an Associate Professor in Linguistics and Nordic Studies.

She continues, “We can’t test the whole population in order to affirm that the experiment works, so we need to have a representative group, a sample, that is good enough to represent the general population so we can trust it. As the general population, the sample needs to be variable enough (we are all different and might behave differently in a given experiment) and large enough, so the results of an experiment demonstrated on a group of participants can generalize to a larger group, to the population.”

“Having more participants means stronger statistical power, and a more representative and more reliable conclusion. Normally, a research project with 150 participants is more impressive than another one with 15 participants,” Peng explains. He is a Postdoctoral Fellow at MultiLing, working on second language acquisition with a focus on speech production.

Thanassi, also a member of the multidisciplinary Centre for Research on Equality and Education, adds, “From the point of view of my research focus [in special needs education], diversity is important to ensure we are not blindsided toward non-representative findings and conclusions that do not fully address the complexity of the human mind. A diverse recruitment process across schools is also important to ensure that the fruits of our practical efforts reach those that truly need them most, and not necessarily those that are mainstream.”

Becoming a Better Reader and Learner

Did you know that fMRI machines are so loud that you have to wear earplugs when you’re inside the tube? Or that, as a research participant, you sometimes have to fight to keep your eyes open during repetitive tasks? When I went in for my first study involving pain and the administration of electrical shocks, I had cinematic visions of medieval torture chambers and 1960s-era psychiatric hospitals. Instead, I got a band around my forearm and a consultation session with my researcher to decide how much was too much.

Addressing the need for familiarity with equipment and procedures, Franziska, our Socio-Cognitive lab manager, says, “Since it requires a lot of know-how and knowledge to conduct eye-tracking experiments, we have created EyeHub, a network that brings together researchers, technical staff, and students across different faculties and departments and organizes lectures, workshops, and trainings. To promote the use of eye-tracking or pupillometry among students, we offer scholarships for MA students at UiO who use this method in their thesis.”

Having first-hand experience with the processes and equipment described in scientific journals can help one to become a better reader of experimental studies. Most of the published research out there is subject to restrictive word counts, meaning that a lot of detail gets pushed to the side. Right or wrong, the burden of understanding is often transferred to the reader, who may or may not get all the nuances when it comes to specialized machinery and investigatory protocols. When I’m trying to do a critical read of a study, personal experience better allows me to picture what was actually happening in the room when the study was being conducted.

Mental load and task confusion is one issue I pay attention to – are subjects able to adequately understand and practice what is being asked of them? I’m making this next part up and am exaggerating some, but have certainly experienced my share of challenging (and sometimes absurd) experimental scenarios:

Stare at the dot at the center of the screen and try not to move your head, as we’ll have to start the experiment all over again if you do. When an X appears, use your left thumb to press a specific button placed outside of your visual range. When a Y appears, tap your right foot three times and use your right index finger to point to the word “arugula,” except for when the Y is yellow and the X is red. When the X is red, tap your foot twice and point to the word “argosy.” When the Y is yellow, use your left thumb to press another button outside of your visual range. In the next trial, you will be asked to reverse all of the above responses, and we will alternate these conditions repeatedly over the next sixty minutes while you solve these geometry problems. In addition, a loud static noise with unrelated words whispered just below range will be piped into your headset. Try to pay attention, as you’ll be asked to remember this list of words later.

These kinds of instructions might be fine if the intent is in fact to study the effects of something like cognitive load, but they can also reveal a lack of clarity that could have an impact on research findings.

Issues like mental fatigue and boredom don’t typically get a lot of real estate in published work, but it raises some questions for me when I see a study that involves a lot of back-to-back cognitive puzzles or task repetition. As a research subject, despite trying to do my best to stay attentive, I know these are conditions under which I sometimes feel myself mentally checking out.

Peng agrees that hands-on experience can be beneficial for understanding limitations and thinking through future projects. “Participating in a well-designed experiment means that you get a good model to learn from.” He adds, “However, you may also experience something unclear, uncomfortable, or even unacceptable. This is what you should avoid in your own design. For instance, during my MA studies, I participated in a 4 hour EEG experiment at a research center (to make some money). But, I was not happy with the long experiment session. I remembered from the 2nd hour on, I couldn’t maintain my attention to the stimuli. Fortunately, I hadn’t started my first experiment by then. What I got from the experience was that, do not design a session longer than 1 hour. If you have to, then, 1.5 hours would be the max.”

Peng also suggests that there are other kinds of insights one can acquire by volunteering to be a research subject. “Participating in a study is not just 'you come here and do the task and leave,' but rather you communicate with the experimenter. As the experimenter, I am very happy to provide any suggestions or advice to my participants on how to improve their learning. Especially when I do Chinese as a second language – this is a good chance for Chinese learners to get some native input.”

Becoming a Better Researcher

I find it comforting to meet the people responsible for generating scientific knowledge, to know that they snag their sweaters, for example, and lose their keys and go to music festivals on the weekend. They know a lot about their fields, but like me, researchers are human beings

Being a research participant has been weirdly grounding, as I’ve learned that the creation of knowledge is a uniquely human endeavor. There is very little authorial presence in most studies of a quantitative nature, making it appear as if the research has just happened, as if the facts have miraculously uncovered themselves under just the right set of conditions. I find it comforting to meet the people responsible for generating scientific knowledge, to know that they snag their sweaters, for example, and lose their keys and go to music festivals on the weekend. They know a lot about their fields, but like me, researchers are human beings, and I think it’s good to be reminded of this. All research happens within a context.

In the US and here in Norway, I’ve had the opportunity to work with data collection on multiple occasions, both in the field and in the lab. From this side, I’ve learned up-close what kinds of research protocols are “worky” and which might be challenging to explain. I’ve also learned that it’s hard to account for every possible variable, and that things that might be relevant sometimes go unmeasured for the sake of focus. “Or logistics/resources (mostly, time, I would guess),” Thanassi adds.

Mainly, though, I’ve come to understand that research represents a significant investment of time for those who do it. In addition to setting up the experimental paradigm, getting ethics approval and funding, generating materials, and doing data analysis (all monumental tasks in themselves), researchers (and/or their assistants) spend hundreds of hours recruiting, scheduling, and then running those who show up through the process. From here, it’s not much of a leap to the conclusion that research dedicated to improving or better understanding the human condition simply just can’t happen without participants.

Natalia, who works with research on infants’ early language acquisition, invites parents to come to the lab and learn about the milestones of monolingual and bilingual language development. She sees subjects as an active part of the research process: “Participants can be the source of inspiration for new societally relevant research projects: by participating in the projects, they can reflect, together with the researchers, on the aims of the research and the research methods and provide input from a more ‘naïve’ perspective. After all, simple (‘naïve’) questions are the most difficult but also the most important to answer; many times the questions addressed by our participants have led to the birth of new research projects.”

In both quantitative and qualitative research, participants have a critical role in shaping the kinds of questions that get asked and answered in scientific fields. “Research for and with people will change both the researcher and the research participants. I hope that my research has contributed to Kven people valuing their language and culture,” says Pia. “Researchers have a responsibility to listen to the communities in which we work and reflect on our own work and positioning. Through such mutual engagement, I believe, we get deeper insights which in turn leads to better research. But such engagement takes time and requires that we listen, so it is important to set aside time and energy.”

Finding a Sense of Wonder

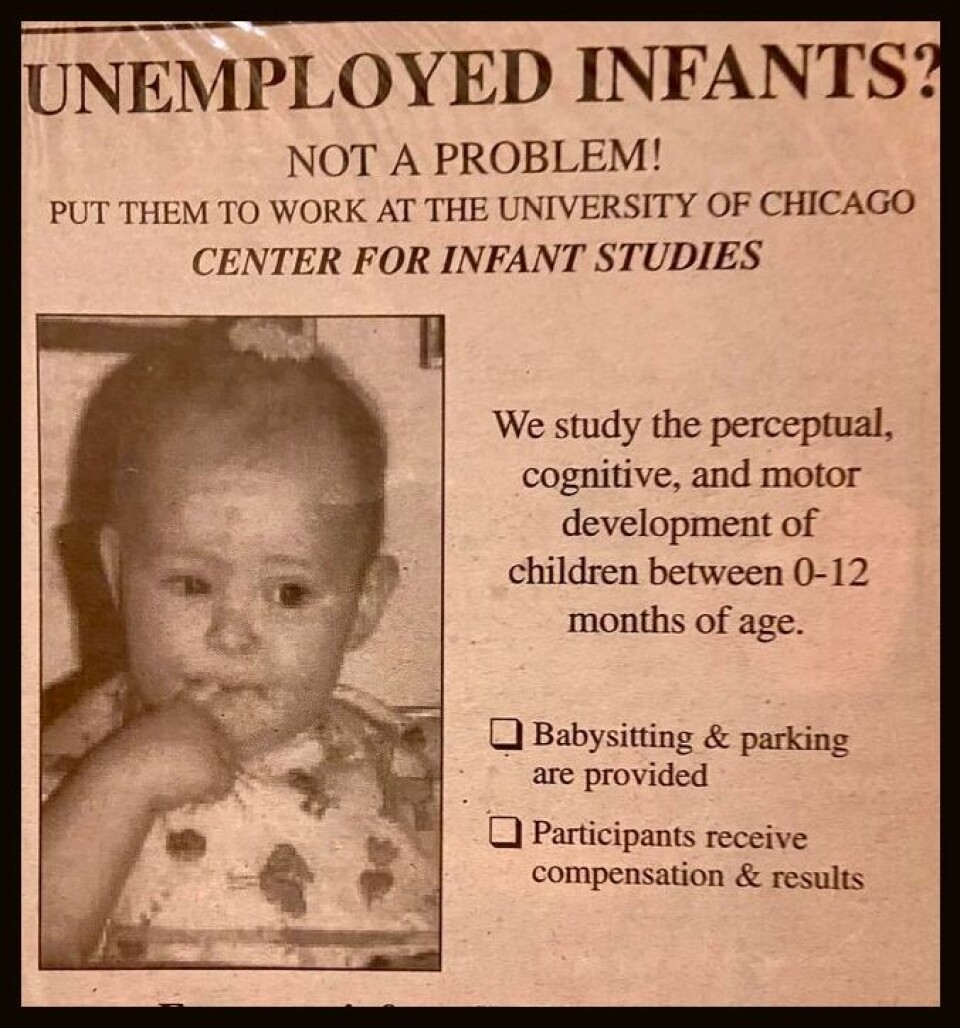

The first time I ever ran a lab-based experiment, during an MA program years ago, was when I was pregnant. This experience was still fresh in my mind when, not long after my child was born, an ad in the student paper recruiting “unemployed” infants for developmental studies caught my attention.

Once a week or so with the stroller, we’d walk the five blocks to the lab. The research assistants were good with little ones and great at explaining what the studies would entail. I was always in the room and found myself filled with a sense of wonder at discovering what this child-sized brain was up to. When she was engaged, her eyes would widen and she’d open and shut her hands, dance her feet around. She seemed to enjoy participating, or at the very least, did not find it unpleasant. Afterwards, instead of gift cards, they’d give her a little toy, like a rubber duck, as compensation for her efforts.

To this day, when I run across a study I think she might have been in, I send my now-adult child the abstract and ask, “Does this ring a bell?” The answer is always a raised-eyebrow “No?” but I do it anyway, to show her that even before she could speak, she was a part of trying to answer some of these critical questions about human life and development. It’s also part of an ongoing joke between the two of us, where I ask her about things she couldn’t possibly remember.

Thanassi, who works with school age children, also notes the benefits families experience from participation: “Because we use a lot of reading and reading-related activities in our procedures, the time spent participating in the study is not ‘time lost’ from school for the child, but can be considered additional reading practice, all the while the child is typically enthusiastic. They get individual attention by a highly-trained research assistant who loves working with kids, the use of attractive, age-appropriate materials and apps, and – not least – the eye tracking equipment that registers where they look on the computer screen. As we typically observe, participating in our study is a fun and productive experience for the children, who are eager to tell their classmates and encourage them to participate as well.”

At the BabyLing Lab, Julien agrees that participating “is a fun activity to do with your child (my young children never missed an opportunity to 'test out' a new study!) and young participants are always happy to receive a small gift for their participation and a picture of them in the lab!”

He adds, “We couldn’t learn about how children learn languages without the generous participation of parents and their children – and for that, we are grateful… We currently have an important study, looking into the role of fathers on the development of their young children. All of our studies are perfectly safe (we will typically evaluate where a child looks while looking at visual scenes – using a special camera that monitors eye movements) and the child will always stay with their parent, or in their sight. Fathers can sign up here or drop us an email at baby-ling@psykologi.uio.no.”

Consenting to Participate

Participants must give their consent at the beginning of each experiment – if they later decide to revoke their consent, that is totally possible and has no negative consequences for them at all.

“As a researcher in Second Language Acquisition,” says Peng, “I really want to encourage people to take active participation in L2 studies. Perhaps due to personality reasons (shy), socio-cultural reasons (avoiding criticism, as much L2 research addresses insufficiencies of learning), or just lack of interest, we often face challenges in getting enough participants. In longitudinal studies [which require a greater investment of time], dropping out is very common.”

“Many of our current studies involve participation of young infants and toddlers,” says Natalia. “Although many parents do bring their kids to the lab, some parents might feel reluctant to involve children in research. We would like to mention that all our research follows strict procedures for data protection and storage, our methods are safe and non-invasive and all research projects are approved by an ethical committee and data protection and share agency SIKT before they can run in a lab. So you can be sure that your kids are in safe and good hands.”

When you show up for an experiment, you’ll be given a consent form with information about the study and what you can expect. “Participants must give their consent at the beginning of each experiment – if they later decide to revoke their consent, that is totally possible and has no negative consequences for them at all.” Franziska adds, “Personal data of participants is only used for the purpose of the study and will be treated confidentially and in line with data protection regulations. Furthermore, only anonymised data which cannot be traced back to individuals, will be shared with the research community. There are no real risks involved in participating in our studies.”

After reading the consent form, you’ll have the opportunity to ask any questions that might have come up for you. Ask away if you have any doubts or concerns, and remember that you are free to withdraw at any time.

As an international student, if you don’t speak Norwegian, you’ll likely want to be on the look-out for studies that offer experiments in English (or another language that you speak). If you’re interested in joining a study at MultiLing, check out current studies on the website and/or register to join the participant pool. You can also check out the list of projects happening at the Department of Psychology here or by exploring project pages in other departments. Franziska also recommends keeping your eyes open for opportunity, “as many studies try to recruit participants with posters on campus or on Facebook pages for students.”