How East Europe Is Resisting Fascism

Silence and fear have become tools against civil disobedience in Russia and Belarus. Who are the people still standing against totalitarianism?

Not too far from Norway, political dissent is in danger. Every day more and more activists in eastern Europe are jailed, prosecuted or silenced because of the ideas they voice. Rights and freedoms that we have taken for granted are disappearing from some, and in these countries it is the responsibility of students and activists to keep them alive against authoritarian politics and fascism.

With the steady rise of violations of freedom of expression and the increase of political persecution in eastern Europe, Universitas dives into the reasons behind political activism in times where fear and persecution loom over people's heads—home and abroad.

The danger of ideas

– I don’t have a big following on social media, but still I fear that what I post could be leaked, says Toni.

Toni (name changed to conceal identity) is a former teacher from Russia who came to Norway to study because of concerns for his safety. His exile was motivated by the turn his home country was taking in the prosecution of protesters and dissenters. His reasons for fearing persecution are justified:

– I once made a joke online, a post with a joke. Afterwards my father in Russia called me to say that someone had called him from an anonymous number and asked him if he had any problems.

Toni now lives far away from Russia, but if he were to return he would need to take extreme care to mask his digital footprint. Being vocal online may be dangerous to activists, as surveillance can turn your most private and well kept secrets into something to use against you.

– I have an LGBT friend from Chechnya. When she crossed the border, she was investigated by an FSB agent and almost got in trouble because of the content on her phone.

Repression of public protests

Toni recounts that in 2021, amidst the turbulence of the COVID crisis, the Russian government found a plausible excuse to tighten its grip over the political views of Russians. According to him, the process had however started earlier.

– The government introduced a law stating that protest organisers now needed to apply for permits. They justified it by saying it was due to COVID, but this was already 2021. It was obviously just biased and targeted towards political enemies, he says.

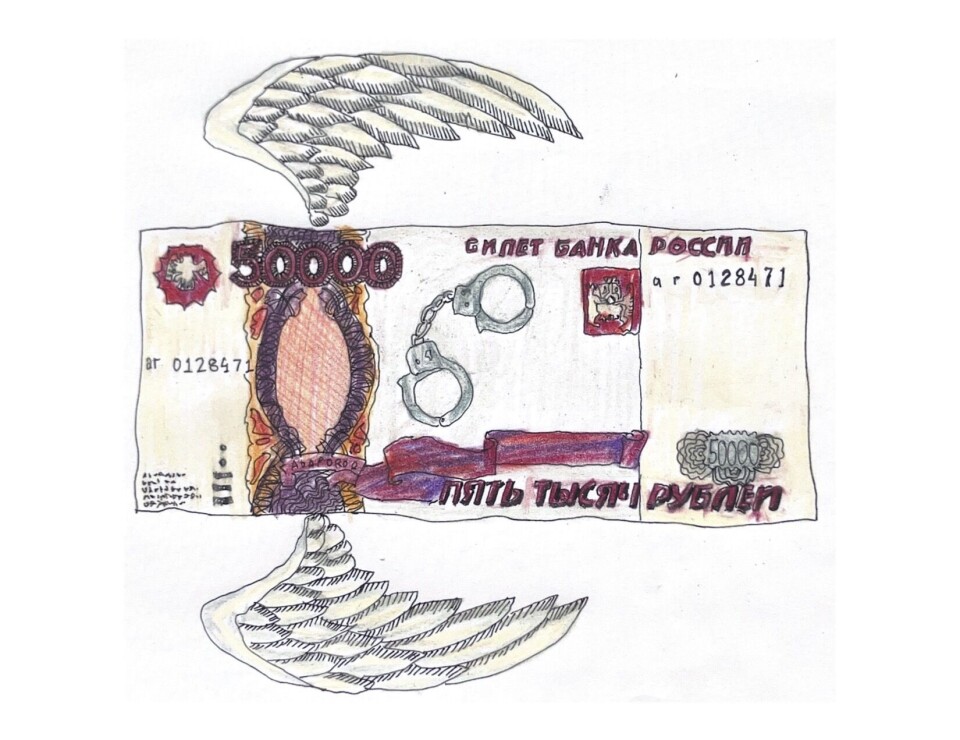

Protesting in Russia can lead to heavy fines or detention. These measures haven’t stopped tens of thousands of people across the country from voicing political ideas that challenge Putin's government. Tony participated in several protests against pension reforms and the imprisonment of the opposition politician Alexei Navalny. Even though he says that the protests were peaceful, he was beaten and arrested.

– The police punched me in the nose and detained me. We spent the whole evening in the police department.

The threat of prison

Although Toni managed to avoid a prison sentence, many political activists end up in cells for their views. In the neigbouring Belarus, the situation is dire, as the human rights centre Viasna documents. Viasna provides education, research, and practical support for political prisoners and is foremost in Belarus in actors speaking against the authoritarian turn of the state.

"New political prisoners keep appearing in the country, their treatment is worsening, and prison sentences are becoming longer," said correspondents from Viasna.

One such political prisoner is Marfa Rabkova, who is currently serving 15 years in prison for protesting against Belarusian president Aleksandr Lukashenko. Viasna writes that for prisoners, "Medical care is not provided, inhumane conditions are deliberately created, and guards humiliate and mock people in every possible way".

According to the center, these prisons are made to break the will of people who fight against totalitarian regimes. "At all levels, the penitentiary system does everything possible to exert physical and psychological pressure on individuals."

This manipulation and fear leaks from the prisons into public life and serves as a tool to keep people from trusting and helping each other. "People in Belarus are very frightened and are extremely cautious about any contact. They may feel that no one can help them—not lawyers, human rights defenders, or European representatives". For Toni, the pressure eventually got too high:

– It's like the metaphor of the frog in the boiling pot: when you slowly heat the water, the frog won't feel the change in temperature and boil alive. That was the feeling I had, that things were about to explode, he says.

A speck of light

The picture Viasna and Toni paint is dire, but there is also a speck of light in their stories. Toni recalls what happened after he was detained for protesting, and how he overcame the fear of the repercussions of the Russian state.

– I went to the doctor, documented that moment, and wrote a case against the policemen. I argued my case in the European Court of Justice, and two years after the protest the court decided that the violence in the protest was unjust.

The case Toni is talking about (Sokolov and Others v. Russia) couldn't have been possible if he or the people involved had given up hope and surrendered to the authoritarian demands of the Russian state. As Viasna concludes, "If those who have endured the horrors of imprisonment and unimaginable hardship still haven’t given up, then neither can we—until the last political prisoner is free."