Alpha Crucis:

Lighting up the Norwegian museum scene with a selection of African art

Alpha Crucis, which refers to the brightest star in the constellation, Southern Cross, represents a necessary reorientation.

The exhibit, named after this star only visible in the Southern Hemisphere, asks the viewer to engage with the postcolonial project of reimagining the role of art museums. Astrup Fearnley, which has showcased works from across the globe, including Brazil, India, and China, now showcases art from Senegal, Sierra Leone, South-Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Benin, Nigeria, and Mali.

Billie Zangewa greets museum-goers during the final weekend of Alpha Crucis

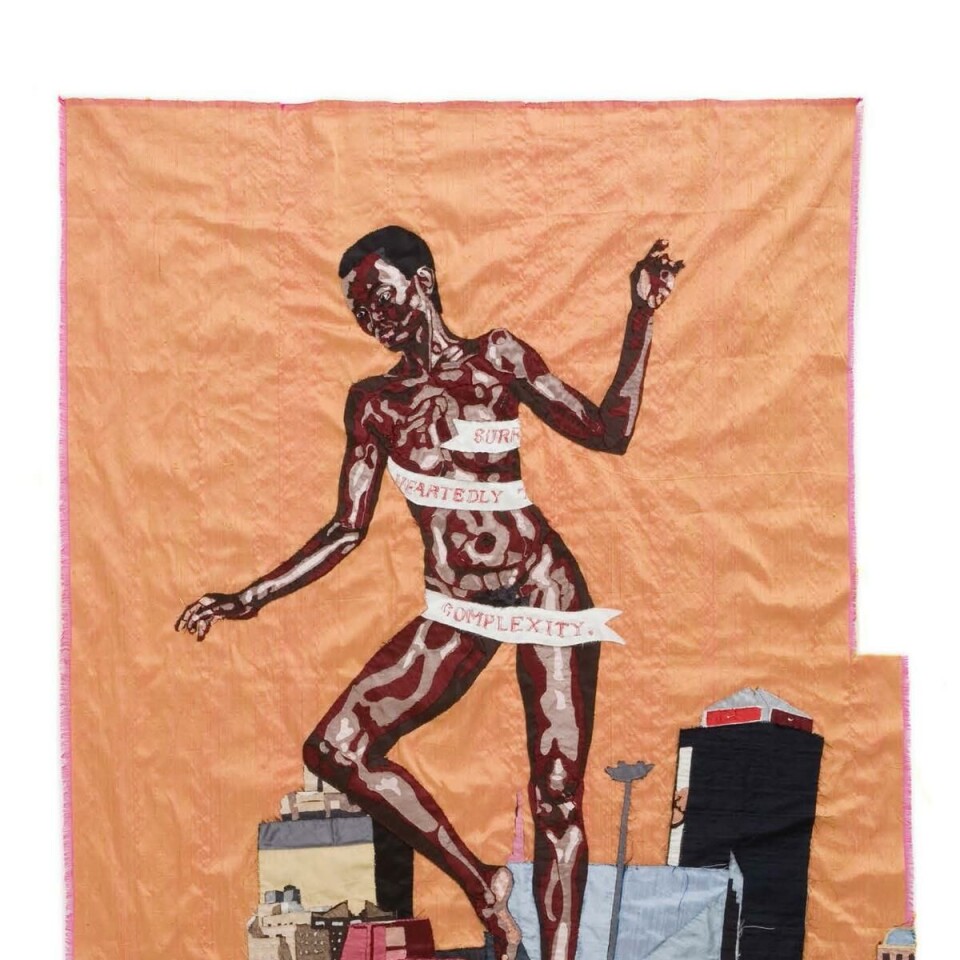

As the viewers entered the first hall of the Alpha Crucis exhibit at the Astrup Fearnley museum, they were greeted immediately by large, colorful textile pieces by the artist, Billie Zangewa. Zangewa, born in Malawi, but grew up in Botswana, currently lives and works in South Africa. Her choice of medium—raw silk stitched together to form tapestries that reveal female figures in context — sheds light on Zangewa’s intention to evoke conversations about gender, as stitching and textile work have historically been relegated to the female domain. Notably, many of Zangewa’s pieces have sections missing — setting her artwork apart from traditional paintings atop a rectangular canvas.

Zangewa’s pieces bring Black women’s narratives and experiences to the forefront. It is particularly poignant that one of the first pieces the viewer is met with plays upon the renaissance painting, «The Birth of Venus», by Sandro Botticelli. Zangewa’s tapestry signals an evolution by subverting the limitations of body size, gender, race, and setting found in Boticelli’s work. Zangewa’s pieces are largely autobiographical—she creates artwork in her own image and draws words from her diary. «The rebirth of the black Venus» (2010) reveals a woman towering over the skyscrapers of Johannesburg with a banner that reads «abandon yourself without reservation to your own complexity» draped across her body.

And complexity the Alpha Crucis exhibit does reveal. In case you missed it, September 6th was the last day of the Alpha Crucis exhibit at the Astrup Fearnley museum located at Tjuvholmen in Oslo. The exhibit, which first aired at the end of January, was closed mid-March due to the COVID-19 pandemic, recently reopened in June for a final summer bang. The final weekend was packed with museum-goers, some masked, and some not.

The exhibit draws together seventeen artists across three generations and from seven Sub-Saharan African countries. Though the exhibit is not nearly comprehensive enough to claim an overview of contemporary art across the entire continent of Africa (which, let me repeat once more for those in the back, is a continent of 54 nations with thousands of languages, diverse communities, and unique lived experiences) — the exhibit is a good first step for introducing the Norwegian audience to the exciting art scene thriving on the African continent.

How post-colonial was the curatorial process?

It is important to note, however, that the curator, André Magnin, is a French, white male. While Magnin has over thirty years of experience working with «non-western» art, it still feels counterintuitive, if not problematic, that an exhibit that wants to shed the colonialist art logic, chose Magnin as the curator, given France’s history of colonialism in the African continent.

Though unfortunately not surprising, it feels as though African voices and perspectives are still excluded from elitist art spaces that are largely dominated by white males.

There is a clear missed opportunity for the exhibit to create the kind of space that might dismantle fine art museums’ complicated and colonialist history by inviting a curator from one of the African countries the exhibit strives to showcase. At the very least, the exhibit could have acknowledged the colonialist underpinnings in its curatorial process, or grapple with what it means to have Magnin serve as the lead curator.

Romuald Hazoumè critiques colonial legacy in Benin

While Alpha Crucis may have missed a beat from a curatorial perspective, the incredible artwork from these seventeen artists cannot be diminished. The exhibit touches on prescient themes that concern the global community—resilience, climate change, gender equity, ethnicity, technology, globalization, and family. Romuald Hazoumè, a sculptural and multi-media artist from Benin is well known for depicting the socio-political context of Benin and the colonialist slave-trade legacy.

The particular pieces included in the exhibit — a wall of mask-like sculptures, half of a car that appears chopped by the gallery wall, and a scooter with green glass jars — depict the narrative of Benin petrol smugglers and their journey across the shared border between Nigeria and Benin. Using the traditional Yoruba masks as a point of departure, Hazoumè creates mask-sculptures out of plastic petrol jerry cans and other found materials to bring light to the resilience, bravery, and ingenuity of these young smugglers.

The vehicles like the car and scooter found in the exhibit depict the sheer amount of petrol these young smugglers carry with them across the border—an easily-ignitable hazard. Not only do these sculptures depict local lived experiences in Benin, but they also spark conversations about Western interference, corruption, and exploitation of the country and surrounding areas.

Both Billie Zangewa and Hazoumè, along with the fifteen other artists included in Alpha Crucis, use their unique experiences, techniques, mediums, and narratives to evoke both conversations about daily life and the long-lasting impact of colonialism. While, as mentioned, there are certain points where one must remain critical of the Alpha Crucis exhibit, the kinds of conversations that these artists encourage the viewers to engage in are worthwhile and will hopefully introduce the necessary space for contemporary African art in the global museum scene.

Photos were retrieved from Astrup Fearnley museum