Fear, loathing, and activism in Putin’s kingdom

ST. PETERSBURG and MOSCOW: While Vladimir Putin tries to suppress all resistance, some people still stand at the barricade.

Vlad stands by himself along Nevsky Prospekt, St. Petersburg’s main street. It’s Friday afternoon, and everyone is rushing on their way to the weekend. No one pays much attention to the young man. That’s not so strange, since all he has is a white, anonymous sign which reads «To remember is to fight. End fascism!». He doesn’t say anything, he doesn’t do anything. He just stands there and lets the sign do the talking. Russian law says people have to maintain 50 meters distance from each other if protesting with signs, so-called «picketing».

Around the lonely anti-fascist-demonstrator is an enormous police presence. Twenty-two riot policemen stand in front of four police vans. They talk to each other, smiling. This is a simple routine. I walk toward Vlad to talk to him.

¬¬«I’m here to mark that the activists who were killed are not forgotten,» he says.

While we are standing there, a policeman walks toward us. He stops when he’s about one meter away, picks up a camera and takes a picture, before he turns around and walks towards his 21 waiting colleagues.

«What’s he doing?»

«The police want an overview of the whole activism environment. I guess they think you’re one of us now,» Vlad says.

«There are a lot of teenage fascists in Russia. I’m here to protest against them. But the police don’t work for the people. They make life hard for the activists.»

Bolotnaya

We also had the chance to talk with young, indignant Russians who dislike current politics but don’t want to protest on the streets.

We talked to several people, but they didn’t want to participate in an interview. They told us they stay home due to fear of retaliation from the security police FSB, formerly the KGB. If you got caught you could lose your right to study or get career opportunities taken away from you, they explained.

That fear is understandable if you read the reports from the Bolotnaya-protests in Moscow in 2012. More than 30 people were arrested, several fled abroad and received political asylum. The Russian government said violent riots had developed at the Botaya-demonstration, while independent observers claimed the protests were peaceful.

Amnesty international has recognized the punishment persecuted as conscience prisoners. By a series of protests in October, 260 people got arrested in an anti-Putin-demonstration in several cities. Similar examples is easy to find – life as an activist isn’t easy in the Russian federation.

«No papers, no problems.»

«You can be put in prison, even when you haven’t done anything wrong. It creates a lot of fear,» Olga Polyakova says.

We meet her at some kind of cafe in St. Petersburg. «Some kind of» because it’s placed in an apartment, well hidden behind a metal door, and we got access to the entrance code shortly before the interview. A group of youth sits in the kitchen and play «Creep» by Radiohead. A violinist and a pianist sit in the living room practicing Monti’s masterpiece «Csárdás». Olga handpicked this place for us to meet.

«I’m trying to not pay tax by only using private hospitals, not buy things inside Russia and use cash. Or by using tax free businesses, like this place,» she says and adds that her mantra is «no papers, no problems.»

Isn’t that a bit disloyal?

«When I explain to people that I don’t pay taxes, it’s always followed by discussions. And I can explain to people where their tax money disappears and why they always end up with empty pockets.»

Twelve days in the cage

Thirty-year-old Olga has been an activist in around five years. She’s one of the founders of the St. Petersburg-based group «Trava.» In english it means something like «grass,» and they primary dealt with drug reforms. Last summer she had her first meeting with the Russian police.

«I got arrested after a completely peaceful protest, as the majority of the protests in this country are. I had to be in jail for twelve days,» Olga says.

The prison visit turned out to be more comfortable than she had feared it would be. She ended up in a two man-cell with her neighbor, and they sneaked in their mobile phones. Nevertheless, the prison time made an impression. She tells us that the police knocked on her door the day after an illegal protest this winter. When she didn’t open, they continued to the next door. It turned out they were after her neighbor.

«I completely panicked. One friend of mine had to come over to comfort me. The activism in Russia is hard since our courts are politically controlled. You can’t count on justice, because the system isn’t made for justice.»

«They are all idiots»

«All of a sudden you can be in a demonstration where the police arrest everyone», says «Ekaterina».

The woman in her fifties wished to be anonymous since she’s afraid it will put her job in the public sector in danger. Nevertheless, she’s been in almost every protest possible these last six years.

«My friends ask me why I put my job in danger, because that will not lead to any change. My parents’ generation was completely silent during the Brezhnev and Putin eras and if my daughter asks me what I did during the Putin era, at least I can tell her I wasn’t silent,» she explains.

«What made you go to the streets for the first time?»

«When Vladimir Putin came up the water in Greece and claimed he found an antique vase by coincidence, I understood that everyone in the Kremlin are idiots. And then I became an activist,» Ekaterian said.

If you’re homosexual in Russia, people say not only are you a pedophile, but you also have every single existing disease.

Sad and hurt

«Are you afraid to get arrested?»

«Of course I am, because then I can lose my job. I’m trying to stay away from the riskiest protests. But all of a sudden you can find yourself in a protest where the police arrest everyone,» Ekaterina said.

She remembers the fall of the Soviet Union, and how everyone around her was optimistic and dared to hope for a brighter future. But it didn’t take many years until «everyone understood that nothing had changed.» But even if Ekaterina talks about herself as a patriot, she is ashamed of the current situation in her country.

«There are so many talented and goodhearted people in Russia. If the country had had a normal political system, I would have lived a completely different life. The thought of this makes me both sad and hurt.»

«Crap law»

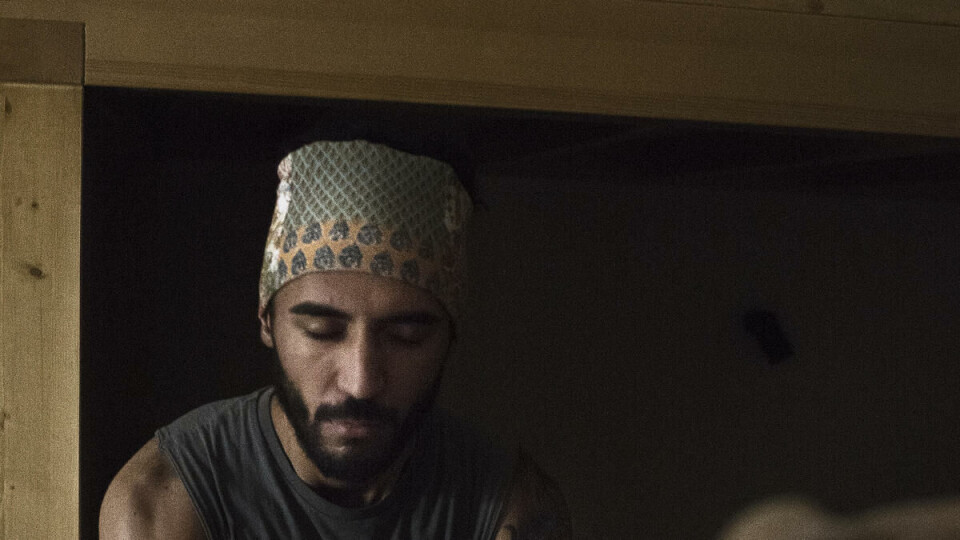

One of the many reasons why Ekaterina continuously takes the streets is Putin’s restrictions on gay rights. In 2013 the anti-gay propaganda started to flow, saying for example that hetero- and homosexual relationships aren’t equal. Maxim Yakubovski is a 26 years old gay man from a small village in Kauksus, and an LBTQ-activist. He used to protest in the streets. Now he is a volunteer in a HIV-center while he completes his PhD.

«You have to respect the law, even if it's a crap law. And the propaganda laws are extremely crap,» Max says.

Strong orthodox church

When Max moved to St. Petersburg as a 16-year-old, it didn’t take long before he came out. But in his home village it was a big disgrace when one of his classmates came out as gay.

«His parents said that he no longer belonged to their family,» Max says.

«What’s the difference between St. Petersburg and your home village?»

«The orthodox church is even stronger in the villages, and they are trying to recreate Russian nationalism, which isn’t compatible with the LBTQ-rights,» Max says.

Even if he lives in the relatively liberal St. Petersburg, far away from Kaukasus and his family, it took a long time before he came out to his mother. When he called her to tell her about his homosexuality, she begged him to not tell his father. He still hasn’t.

Stereotypes against gay people are strong in Russia. Max says the next few years are crucial for the LGBT movement.

«If you’re homosexual in Russia, people say not only are you a pedophile, but you also have every single existing disease.»

Completely apolitical

Despite the age difference and their various causes, Vlad, Olga, Ekaterina and Max are united in active resistance against a regime they believe is unfair. But even if many of the youth in the major cities won’t vote for Putin, few people take the streets.

In Moscow we meet masseuses Anton and Backa. When we enter their apartment, we get hit by a strong scent of incense. The lights are dimmed and the tea pot is whistling. They serve a traditional Russian cake together with the tea. Before the interview they have one premise:

«This apartment is a politics free zone,» Anton says.

«Why?»

«We just don’t care at all. Whatever the Kremlin does has nothing to say for our lives,» he says before Backa stresses they are not Putin-supporters.

The two guys don’t hide their interest for psychedelics, and the conversation turns to energy flow, expanded reality and how to learn within yourself.

«What about liberalization of the drug laws? Isn’t that a political question?»

The question makes them laugh. They say that they won’t «play that game.» No matter who will run for president they will stay home during the day of election.

«As we said, we don’t care about politics,» Anton and Backa say.