Encounter the Ruins of Medieval Oslo

At the hub of the capital, cultural landmarks like the Royal Palace, the National Theater, and Stortinget dominate the cityscape, iconic images conjured automatically when thinking of Oslo.

But imagine, five hundred years from now, that all that’s left of the theater are scraps of its foundations, and the cobbled streets of Karl Johan are buried under centuries of sediment. Imagine the palace has disappeared, and the only evidence remaining of a structure at all is the indentation it left in the earth. Imagine children climbing on the ruins of Stortinget on the way home from school.

It’s an uncanny thought, but one that allows us to approximate what a resident of medieval Oslo might feel, looking across Bjørvika bay now at the crumbling remnants of their city.

Setting Out

Taking the tram on Line 13 to Ljabru, four stops after Nationaltheatret is Middelalderparken – which, as it turns out, is not the same as Minneparken, though they are both dedicated to preserving the remains of medieval buildings and are within walking distance of each other. I’ve been to other medieval sites in the city, the ones you probably already know: Akershus Fortress, the abbey at Hovedøya, but it took me quite a while to make the time to visit Gamle Oslo and experience what it has to offer.

How lovely it is to walk the same trails as those who went before us and invent new meanings for them. How lovely it is to live in history, even if you’re only in Oslo for a semester.

In preparation for my excursion, I read Guide to Gamlebyen and Medieval Oslo by Morten Krogstad, Erik Schia, and Ola Storsletten. Inside, I found not only a guide for the curious

sightseer, but also a vision for a future Oslo, which might more thoughtfully include this part of its history in city planning. The book was published in 1993, nearly thirty years ago, but much of its lament for the current state of conservation is still relevant today.

A Forgotten Past?

Though once the heart of Oslo, the topography of the city separates Gamlebyen from the rest of the capital. The skyline, textured by monuments to modern Norway and cluttered by construction equipment, abruptly falters, leaving in its shadow a maze of stones that used to support the weight of cathedrals and house medieval kings. The motorway cuts between these two versions of Oslo, and work on a new underground rail line interrupts the landscape, breaking the continuity of the park and leaving some sites inaccessible.

This picture of medieval Oslo is one characterized by neglect. However, that’s all the more reason to visit, then, and encounter a part of the city that hasn’t received enough love. Below is a guide to some of the most famous sites in Middelalderparken and Minneparken, drawn from information provided by signs on-site, as well as from Guide to Gamlebyen, which includes even more places to explore than listed here. A digitized copy is available online via UiO’s library.

St. Mary’s Church

After getting off the tram, the sightseer turns right along a sandy footpath and follows it to the very end. Behind a colossal, abandoned workshop from the 1890’s lies what remains of St.

Mary’s Church, which was originally a wooden structure built around the year 1000. It sits adjacent to the ruins of the Royal Farm and served as a chapel to the king – though by the sprawling network of stones it is clear that the structure could have been a cathedral in its own right.

Near the center of the ruins, a plaque is fixed to the ground in memory of King Håkon V, who commissioned the church’s reconstruction in brick around 1300, and was buried there in 1318. His reign established Oslo as the capital of medieval Norway, and his chapel was the keeper of the kingdom’s seal, a symbolic honor that proclaimed Oslo as the seat of Norwegian power. One can imagine him moving amongst the newly reconstructed walls, dressed simply and giving shelter to pilgrims.

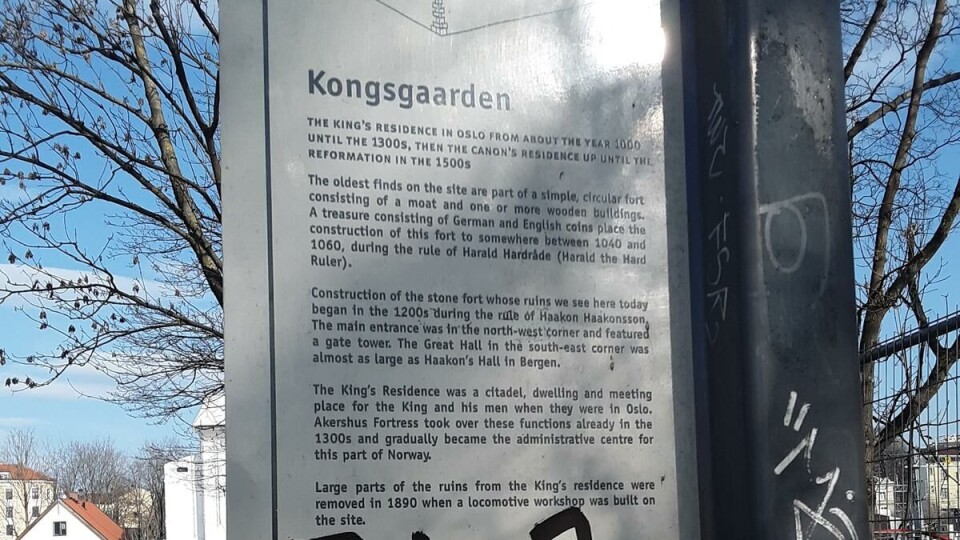

Kongsgården

Before Akershus Fortress, there was the Royal Farm, or Kongsgården in Norwegian. The original wooden structure was built by Harald Hardråda in the mid-eleventh century, a decade or so before his death at Stamford Bridge. But in the 1300s it fell victim to one of the many fires that plagued Oslo during the medieval and early modern periods. It was then rebuilt in stone by Håkon IV, who died a few years before Håkon V was born.

Much of the Royal Farm was demolished when a locomotive workshop was erected in the same area at the end of the nineteenth century, the same one which stands there abandoned today.

Along with the more modern examples of the railroad and motorway, this development from a hundred years ago shows how the medieval city has been eroded by ostensible progress.

Olavsklosteret

Our next stop is Minneparken. Guide to Gamlebyen proposes reviving the old footpath that connected the site with those of Middelalderparken in the Middle Ages, but the construction of the Follobane makes this suggestion an impossibility until the completion of the project.

Though for now you’re unable to traverse the old trail taken by the kings and peasants of centuries past, you will find Olavsklosteret after a short ten-minute walk going straight from the tram stop where we started.

Olavsklosteret was a Dominican monastery built in 1249, during the reign of Håkon IV. Of all the sites contained in Middelalderparken and Minneparken, Olavsklosteret is the most complete, though much of the complex has still decayed. Archeological investigations estimate that there was space for ten to fifteen Dominican brothers to live at the monastery. The discovery of English and Dutch coinage shows engagement in international trade, and the remnants of frescoes found there display a shadow of the monastery’s former wealth.

St. Hallvard’s Cathedral

Our final stop on our tour is St. Hallvard’s Cathedral, which you will find on your way back to the tram from Olavsklosteret. The cathedral was built in the 1100s and hosted the coronations of several kings during its time as an active church. Though St. Hallvard’s no longer has the same imposing height and presence as it did seven hundred years ago, across the street you can see a mural painted in 1989, which imagines the street as it might have looked in the 14th century, with the cathedral defining the skyline.

St. Hallvard, after whom the cathedral is named, is the patron saint of Oslo. He is depicted on the seal of Oslo kommune, holding a millstone in one hand and three arrows in another, symbols of his heroic death and subsequent miracles. He died in Drammen in the mid-eleventh century, around the same time Harald Hardråda commissioned the first version of Kongsgården in Oslo. The cathedral was constructed around a century after Hallvard’s death, and upon its completion his remains were moved from Drammen to Oslo, where his grave became a popular pilgrimage destination. You can read the full story here, or an abridged version posted on a sign by the ruins themselves.

Touching the Medieval

St. Hallvard’s fell into disrepair after the infamous fire of 1624, when the city was moved to the other side of Bjørvika bay, and in 1780 many of its stones were removed to pave roads. Now, the cathedral itself has become a kind of byway. On my visit, I saw a father walking his young son home from school through the ruins, down what would have been the center aisle where the priest, a different kind of father, processed into the cathedral for mass. Though there were a few pieces of trash littering the grass, in the shadow of some of the remaining stones I found the first wildflowers I’ve seen this spring.

One might feel a sense of loss when looking at what remains of Oslo’s medieval city, but at the same time I couldn’t help but find joy in watching life bloom within the ruins. How lovely it is to walk the same trails as those who went before us and invent new meanings for them. How lovely it is to live in history, even if you’re only in Oslo for a semester.

But living in history can often mean that it’s taken for granted, that people don’t think twice about leaving a gum wrapper or an empty beer can behind, or that they deface something without considering the consequences. It can mean that conservation efforts come second, third, or fourth to building a roundabout or digging a tunnel to halve the travel time between Oslo and Ski.

As international students on temporary residence permits, it may seem that there is little we can do to preserve medieval Oslo. However, by giving the old city the attention it deserves, we can reintegrate it into our picture of the capital, and hopefully leave these spaces a little better than we found them.